There is no definitive answer, but here are three things to consider before you invest, writes Morningstar’s Daniel Needham.

We’ve heard questions from many clients about why the market is doing so well right now given how bad the economy is, and whether we will see the lows of March 2020 retested.

They’re good questions, but there might not be clear-cut answers for those who want certainty. We’ll discuss three points embedded in investors’ questions.

Key takeaways

Also, the S&P 500 itself is an agglomeration of other markets, one that changes over time. The composition of the S&P 500 has become increasingly dominated by

stocks that are doing well in the current environment because they benefit from work-from-home consumers or are Internet-related, have strong balance sheets, benefit from globally diversified revenues, or their businesses are defensive by nature (meaning demand for their products is less dependent on the strength of the economy).

Most other stocks are down, some by a lot. So, while it feels like some parts of the market are doing too well currently, other parts are pricing in some negative outcomes for energy companies and banks and outright disaster for airlines, hotels, and cruise lines.

The flaw of averages

This is another example of “the flaw of averages.” When you add market-capweighting—or the fact that larger companies make up more of the total worth of a

market—it’s the flaw of averages on steroids.

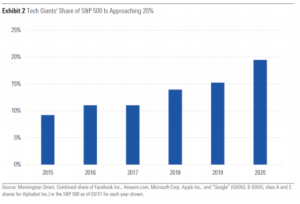

The flaw of averages is illustrated by the man who sticks his feet in the freezer and his head in the oven so he can feel comfortable, on average. To give you a sense of the “the oven” in the US stock market, Exhibit 2 shows the weighting in the S&P 500 of five big tech stocks: Facebook (FB), Amazon.com (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), and Alphabet (GOOG). We think all these firms benefit from the positives being rewarded by today’s markets mentioned earlier—internet-based and global businesses that are benefiting from the work-from-home environment, and they all have strong balance sheets. Even though they’re technology stocks, not defensives, investors aren’t treating them as cyclical stocks.

Also, the S&P 500 itself is an agglomeration of other markets, one that changes over time. The composition of the S&P 500 has become increasingly dominated by

stocks that are doing well in the current environment because they benefit from work-from-home consumers or are Internet-related, have strong balance sheets, benefit from globally diversified revenues, or their businesses are defensive by nature (meaning demand for their products is less dependent on the strength of the economy).

Most other stocks are down, some by a lot. So, while it feels like some parts of the market are doing too well currently, other parts are pricing in some negative outcomes for energy companies and banks and outright disaster for airlines, hotels, and cruise lines.

The flaw of averages

This is another example of “the flaw of averages.” When you add market-capweighting—or the fact that larger companies make up more of the total worth of a

market—it’s the flaw of averages on steroids.

The flaw of averages is illustrated by the man who sticks his feet in the freezer and his head in the oven so he can feel comfortable, on average. To give you a sense of the “the oven” in the US stock market, Exhibit 2 shows the weighting in the S&P 500 of five big tech stocks: Facebook (FB), Amazon.com (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), and Alphabet (GOOG). We think all these firms benefit from the positives being rewarded by today’s markets mentioned earlier—internet-based and global businesses that are benefiting from the work-from-home environment, and they all have strong balance sheets. Even though they’re technology stocks, not defensives, investors aren’t treating them as cyclical stocks.

What does this mean for portfolios?

While we will never have a satisfactory answer to the question of what is driving the market, we do think one can respond to the prices and opportunities presented.

The market is facing a wide range of possible economic outcomes with more uncertainty than usual. In the wisdom-of-the-crowd model, accuracy is driven by the diversity and accuracy of individuals’ guesses. We don’t see anything to suggest a greater diversity among guessers, and most investors would say their guesses have a wider range than normal, so the average accuracy may be much lower than normal.

This means the market’s accuracy may be hindered, and the crowd’s wisdom may have lost a few IQ points. We think it also could mean opportunity for investors

willing to be different from the crowd.

For those businesses whose stock prices are higher than they were at the end of January 2020, one has to wonder whether this environment should call for higher valuations. Mark us as sceptical, but there are still select opportunities.

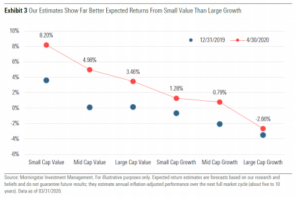

We find those opportunities through our valuation-driven investment approach. Our valuation research leads to calculations of the returns we think an asset class

will experience over each of the next 10 years, averaged and adjusted for inflation.

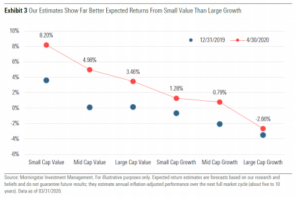

As shown in Exhibit 3, US small-cap value stocks are poised for much higher returns—according to our valuation-based, forward-looking return estimates— than US large-cap growth stocks.

What does this mean for portfolios?

While we will never have a satisfactory answer to the question of what is driving the market, we do think one can respond to the prices and opportunities presented.

The market is facing a wide range of possible economic outcomes with more uncertainty than usual. In the wisdom-of-the-crowd model, accuracy is driven by the diversity and accuracy of individuals’ guesses. We don’t see anything to suggest a greater diversity among guessers, and most investors would say their guesses have a wider range than normal, so the average accuracy may be much lower than normal.

This means the market’s accuracy may be hindered, and the crowd’s wisdom may have lost a few IQ points. We think it also could mean opportunity for investors

willing to be different from the crowd.

For those businesses whose stock prices are higher than they were at the end of January 2020, one has to wonder whether this environment should call for higher valuations. Mark us as sceptical, but there are still select opportunities.

We find those opportunities through our valuation-driven investment approach. Our valuation research leads to calculations of the returns we think an asset class

will experience over each of the next 10 years, averaged and adjusted for inflation.

As shown in Exhibit 3, US small-cap value stocks are poised for much higher returns—according to our valuation-based, forward-looking return estimates— than US large-cap growth stocks.

We chose to show these valuation-implied return forecasts for US small value versus US large growth to stick with the theme above. We’re also seeing similar gaps between US and international stocks and among sectors, with the energy and financials sectors being priced for the best returns, according to our calculations.

In our opinion, market-timing is not possible, however, we think the returns for value, international, and energy stocks in US dollars at current prices look attractive for a long-term US investor.

We chose to show these valuation-implied return forecasts for US small value versus US large growth to stick with the theme above. We’re also seeing similar gaps between US and international stocks and among sectors, with the energy and financials sectors being priced for the best returns, according to our calculations.

In our opinion, market-timing is not possible, however, we think the returns for value, international, and energy stocks in US dollars at current prices look attractive for a long-term US investor.

- Markets are unpredictable, especially in the short term. This means we should be prepared to see many different outcomes, including what we’ve seen in recent months.

- Markets predict the economy, not the other way around. Don’t expect the economy to improve because the stock market has risen.

- What is a market? An index’s performance can hide the idiosyncrasies of underlying sectors and types of stocks.

- In our view, stocks that have fallen more or recovered less often have greater potential for future gains.

Also, the S&P 500 itself is an agglomeration of other markets, one that changes over time. The composition of the S&P 500 has become increasingly dominated by

stocks that are doing well in the current environment because they benefit from work-from-home consumers or are Internet-related, have strong balance sheets, benefit from globally diversified revenues, or their businesses are defensive by nature (meaning demand for their products is less dependent on the strength of the economy).

Most other stocks are down, some by a lot. So, while it feels like some parts of the market are doing too well currently, other parts are pricing in some negative outcomes for energy companies and banks and outright disaster for airlines, hotels, and cruise lines.

The flaw of averages

This is another example of “the flaw of averages.” When you add market-capweighting—or the fact that larger companies make up more of the total worth of a

market—it’s the flaw of averages on steroids.

The flaw of averages is illustrated by the man who sticks his feet in the freezer and his head in the oven so he can feel comfortable, on average. To give you a sense of the “the oven” in the US stock market, Exhibit 2 shows the weighting in the S&P 500 of five big tech stocks: Facebook (FB), Amazon.com (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), and Alphabet (GOOG). We think all these firms benefit from the positives being rewarded by today’s markets mentioned earlier—internet-based and global businesses that are benefiting from the work-from-home environment, and they all have strong balance sheets. Even though they’re technology stocks, not defensives, investors aren’t treating them as cyclical stocks.

Also, the S&P 500 itself is an agglomeration of other markets, one that changes over time. The composition of the S&P 500 has become increasingly dominated by

stocks that are doing well in the current environment because they benefit from work-from-home consumers or are Internet-related, have strong balance sheets, benefit from globally diversified revenues, or their businesses are defensive by nature (meaning demand for their products is less dependent on the strength of the economy).

Most other stocks are down, some by a lot. So, while it feels like some parts of the market are doing too well currently, other parts are pricing in some negative outcomes for energy companies and banks and outright disaster for airlines, hotels, and cruise lines.

The flaw of averages

This is another example of “the flaw of averages.” When you add market-capweighting—or the fact that larger companies make up more of the total worth of a

market—it’s the flaw of averages on steroids.

The flaw of averages is illustrated by the man who sticks his feet in the freezer and his head in the oven so he can feel comfortable, on average. To give you a sense of the “the oven” in the US stock market, Exhibit 2 shows the weighting in the S&P 500 of five big tech stocks: Facebook (FB), Amazon.com (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), and Alphabet (GOOG). We think all these firms benefit from the positives being rewarded by today’s markets mentioned earlier—internet-based and global businesses that are benefiting from the work-from-home environment, and they all have strong balance sheets. Even though they’re technology stocks, not defensives, investors aren’t treating them as cyclical stocks.

What does this mean for portfolios?

While we will never have a satisfactory answer to the question of what is driving the market, we do think one can respond to the prices and opportunities presented.

The market is facing a wide range of possible economic outcomes with more uncertainty than usual. In the wisdom-of-the-crowd model, accuracy is driven by the diversity and accuracy of individuals’ guesses. We don’t see anything to suggest a greater diversity among guessers, and most investors would say their guesses have a wider range than normal, so the average accuracy may be much lower than normal.

This means the market’s accuracy may be hindered, and the crowd’s wisdom may have lost a few IQ points. We think it also could mean opportunity for investors

willing to be different from the crowd.

For those businesses whose stock prices are higher than they were at the end of January 2020, one has to wonder whether this environment should call for higher valuations. Mark us as sceptical, but there are still select opportunities.

We find those opportunities through our valuation-driven investment approach. Our valuation research leads to calculations of the returns we think an asset class

will experience over each of the next 10 years, averaged and adjusted for inflation.

As shown in Exhibit 3, US small-cap value stocks are poised for much higher returns—according to our valuation-based, forward-looking return estimates— than US large-cap growth stocks.

What does this mean for portfolios?

While we will never have a satisfactory answer to the question of what is driving the market, we do think one can respond to the prices and opportunities presented.

The market is facing a wide range of possible economic outcomes with more uncertainty than usual. In the wisdom-of-the-crowd model, accuracy is driven by the diversity and accuracy of individuals’ guesses. We don’t see anything to suggest a greater diversity among guessers, and most investors would say their guesses have a wider range than normal, so the average accuracy may be much lower than normal.

This means the market’s accuracy may be hindered, and the crowd’s wisdom may have lost a few IQ points. We think it also could mean opportunity for investors

willing to be different from the crowd.

For those businesses whose stock prices are higher than they were at the end of January 2020, one has to wonder whether this environment should call for higher valuations. Mark us as sceptical, but there are still select opportunities.

We find those opportunities through our valuation-driven investment approach. Our valuation research leads to calculations of the returns we think an asset class

will experience over each of the next 10 years, averaged and adjusted for inflation.

As shown in Exhibit 3, US small-cap value stocks are poised for much higher returns—according to our valuation-based, forward-looking return estimates— than US large-cap growth stocks.

We chose to show these valuation-implied return forecasts for US small value versus US large growth to stick with the theme above. We’re also seeing similar gaps between US and international stocks and among sectors, with the energy and financials sectors being priced for the best returns, according to our calculations.

In our opinion, market-timing is not possible, however, we think the returns for value, international, and energy stocks in US dollars at current prices look attractive for a long-term US investor.

We chose to show these valuation-implied return forecasts for US small value versus US large growth to stick with the theme above. We’re also seeing similar gaps between US and international stocks and among sectors, with the energy and financials sectors being priced for the best returns, according to our calculations.

In our opinion, market-timing is not possible, however, we think the returns for value, international, and energy stocks in US dollars at current prices look attractive for a long-term US investor.