Inflation is trending lower, and central banks seem eager to cut interest rates. The stock market moves quickly, and interest rate-sensitive stocks like REITs, financials, and consumer cyclicals have rallied strongly in the past six months. This trend could continue for a while, and we still see plenty of value in good-quality stocks in these sectors. However, there is a significant risk that inflation will pick up again as it has in prior decades. While higher interest rates associated with the post-covid-19 burst of inflation were the leading cause of the 2023 stock market correction, stocks can do well in inflationary periods, particularly companies with strong pricing power and reasonable financial leverage.

Plenty of factors are at play that could lift prices for goods and services. Lower interest rates, or even hopes of lower interest rates, will likely spur pent-up consumer demand here and abroad. Western companies are shifting their manufacturing away from China towards friendlier nations, incurring additional costs. Container freight rates are rising again as demand recovery meets limited idle ship capacity, combined with geopolitical risks in certain areas. According to Trading Economics, the Containerized Freight Index, which tracks the cost of shipping containers on major routes, has increased 160% in the past year.

Immigration to Australia is forecast to remain high, which is a nightmare for renters, given residential vacancy rates are already very low. The immense investment needed from the private sector and the government for the renewable energy transition, highlighted again by the recent Federal Budget, will likely keep upward pressure on skilled labour and components. Base metal prices, which are useful in the global renewables transition, like copper, nickel, zinc, and manganese, are rising strongly. Government spending on social programs like the National Disability Insurance Scheme shows no sign of abating. And sadly, global conflict is rising, which can be highly inflationary as resources and people are used for destructive purposes.

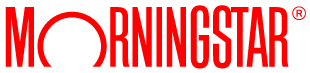

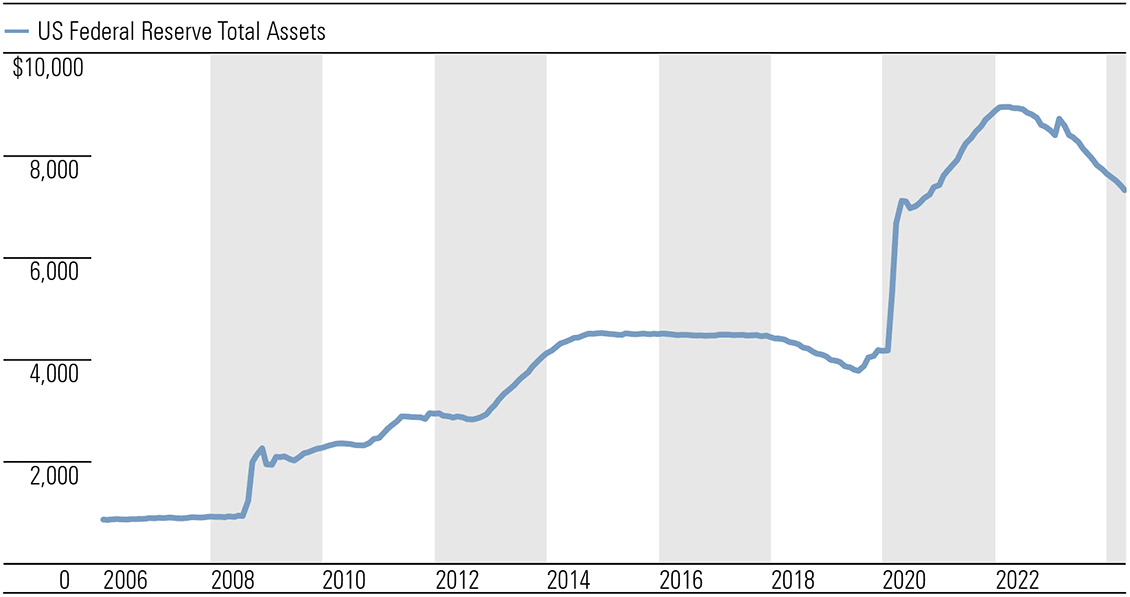

However, a return of high inflation wouldn’t necessarily be bad for stocks. If we look at the 1970s (using United States data because of difficulty sourcing reliable Australian data), the initial wave of inflation caused the stock market to fall sharply in 1974. The market recovered a year later as inflation waned, dipping briefly when the second wave of inflation started before generally moving higher for the rest of the decade despite ongoing inflation (Exhibit 1). The stock market rally continued until the early 1980s, when high interest rates eventually triggered a recession.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Standard & Poor’s, Haver Analytics.

If we experience a re-emergence of high inflation, the best-performing stocks would likely be those with economic moats, whose profits are more likely to keep up with inflation, and those with manageable debt levels that won’t be crushed if interest rates rise materially. Commodity producers, including precious and base metal miners and energy companies, could also do well.

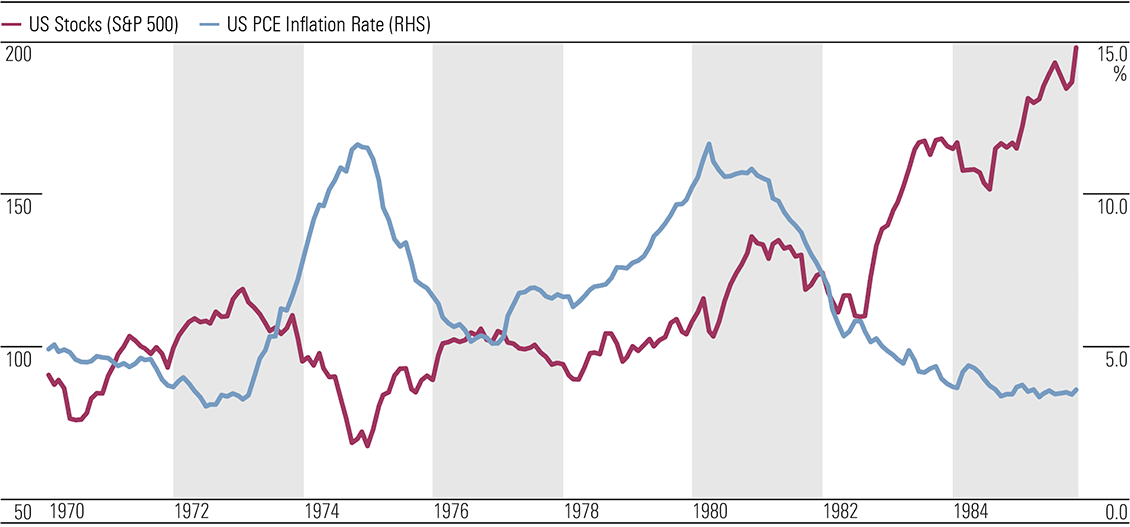

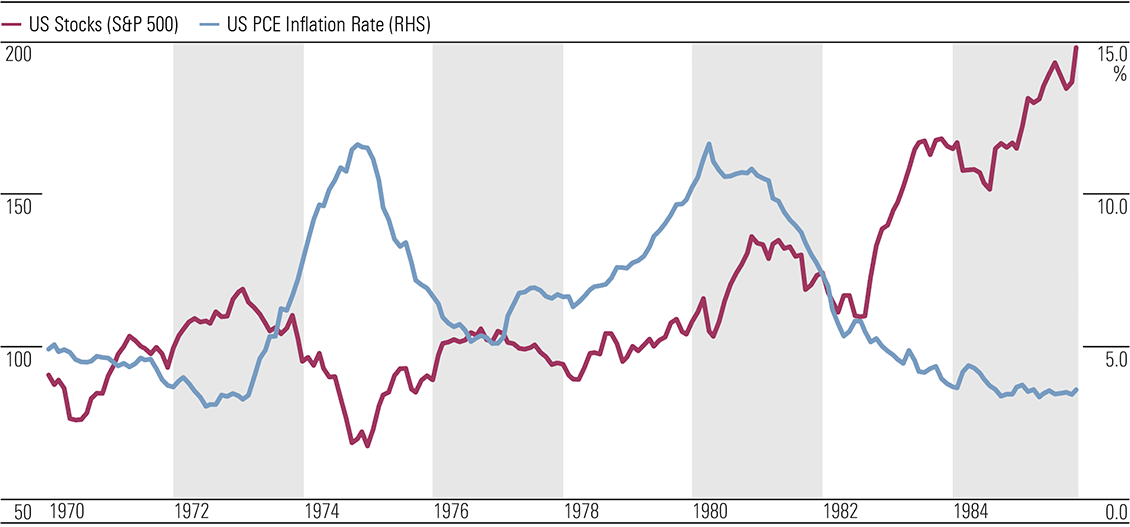

Bonds, on the other hand, performed poorly throughout most of the 1970s. Exhibit 2 shows bond yields, which move inversely to prices, rising in the first wave of inflation and spiking higher in the second. A similar outcome is possible if a second wave of inflation hits this decade, with long-dated fixed-rate debt most at risk.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Standard & Poor’s, Haver Analytics.

If we experience a re-emergence of high inflation, the best-performing stocks would likely be those with economic moats, whose profits are more likely to keep up with inflation, and those with manageable debt levels that won’t be crushed if interest rates rise materially. Commodity producers, including precious and base metal miners and energy companies, could also do well.

Bonds, on the other hand, performed poorly throughout most of the 1970s. Exhibit 2 shows bond yields, which move inversely to prices, rising in the first wave of inflation and spiking higher in the second. A similar outcome is possible if a second wave of inflation hits this decade, with long-dated fixed-rate debt most at risk.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Treasury, Haver Analytics.

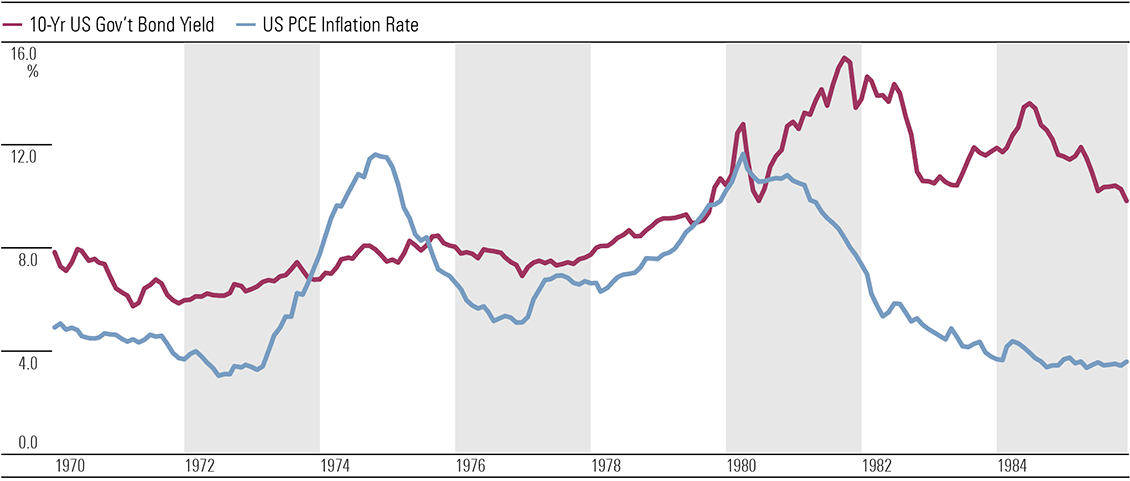

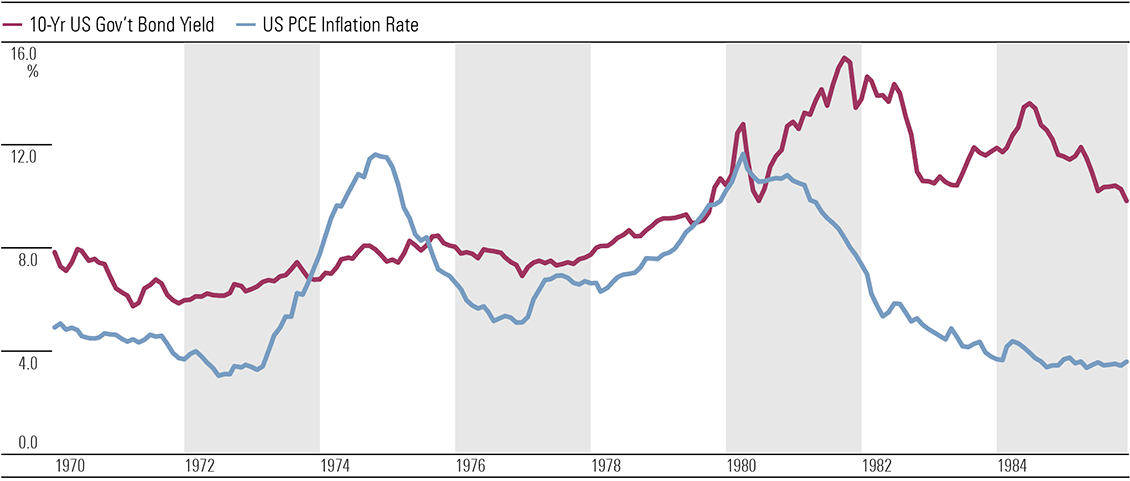

It’s not just inflation that could undermine bond values. Demand and supply could also play a part. Elevated government spending and refinancing existing heavy debt loads across most of the Western world should keep the bond supply high. At the same time, demand from some buyers appears to have disappeared. The US seized about USD 300 billion in Russian foreign assets (state and private property held in the West) when it invaded Ukraine in early 2022. Regardless of whether the confiscation of assets was morally justified, the unintended consequence is that nations that are not fully aligned with the US, like Russia and China, are likely now reluctant to buy Western assets. This is particularly true for government bonds, which can be easily confiscated and help fund a potential military adversary. China’s ownership share of US Treasury Securities has fallen sharply since early 2022 (Exhibit 3), with friendlier nations, including the United Kingdom and Canada, making up the difference for now. China’s central bank and those in Russia, Turkey, and India, among others, are increasing exposure to gold bullion and other assets instead.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Treasury, Haver Analytics.

It’s not just inflation that could undermine bond values. Demand and supply could also play a part. Elevated government spending and refinancing existing heavy debt loads across most of the Western world should keep the bond supply high. At the same time, demand from some buyers appears to have disappeared. The US seized about USD 300 billion in Russian foreign assets (state and private property held in the West) when it invaded Ukraine in early 2022. Regardless of whether the confiscation of assets was morally justified, the unintended consequence is that nations that are not fully aligned with the US, like Russia and China, are likely now reluctant to buy Western assets. This is particularly true for government bonds, which can be easily confiscated and help fund a potential military adversary. China’s ownership share of US Treasury Securities has fallen sharply since early 2022 (Exhibit 3), with friendlier nations, including the United Kingdom and Canada, making up the difference for now. China’s central bank and those in Russia, Turkey, and India, among others, are increasing exposure to gold bullion and other assets instead.

Source: US Treasury. Data as of April 30, 2024.

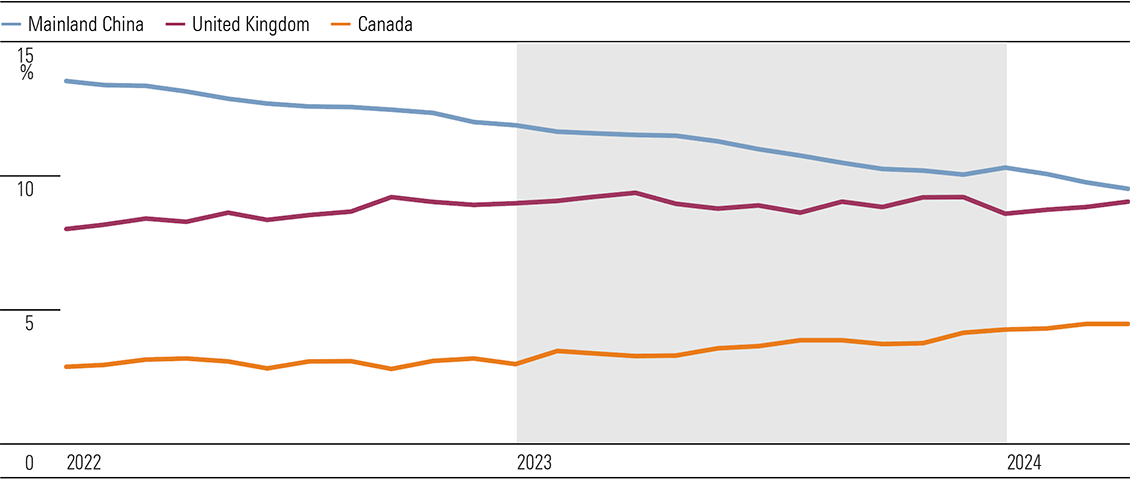

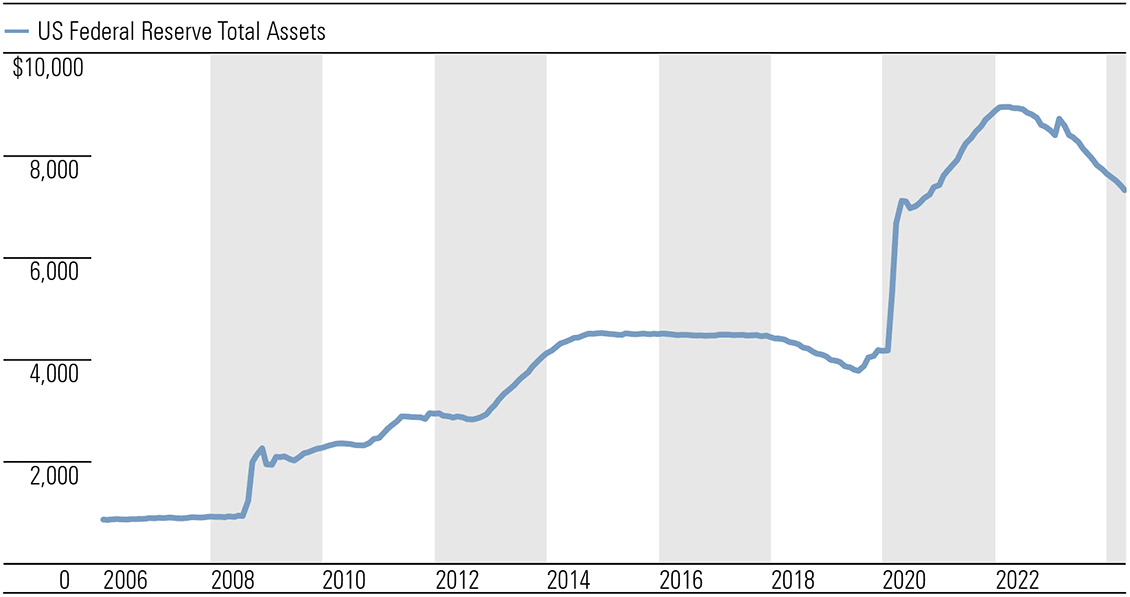

Currently, developed market central banks are draining the liquidity they pumped into the financial system in 2020 with quantitative easing (printing money to buy government bonds). With governments unlikely to cut spending materially and reduced appetite for bonds from China et al, central banks may be forced to resort to quantitative easing again, with potentially positive implications for stock markets and inflation. (Exhibit 4)

Source: US Treasury. Data as of April 30, 2024.

Currently, developed market central banks are draining the liquidity they pumped into the financial system in 2020 with quantitative easing (printing money to buy government bonds). With governments unlikely to cut spending materially and reduced appetite for bonds from China et al, central banks may be forced to resort to quantitative easing again, with potentially positive implications for stock markets and inflation. (Exhibit 4)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Data as of May 15, 2024.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Data as of May 15, 2024.

Exhibit 1: Stocks fared relatively well in the second wave of inflation in the 1970s

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Standard & Poor’s, Haver Analytics.

If we experience a re-emergence of high inflation, the best-performing stocks would likely be those with economic moats, whose profits are more likely to keep up with inflation, and those with manageable debt levels that won’t be crushed if interest rates rise materially. Commodity producers, including precious and base metal miners and energy companies, could also do well.

Bonds, on the other hand, performed poorly throughout most of the 1970s. Exhibit 2 shows bond yields, which move inversely to prices, rising in the first wave of inflation and spiking higher in the second. A similar outcome is possible if a second wave of inflation hits this decade, with long-dated fixed-rate debt most at risk.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Standard & Poor’s, Haver Analytics.

If we experience a re-emergence of high inflation, the best-performing stocks would likely be those with economic moats, whose profits are more likely to keep up with inflation, and those with manageable debt levels that won’t be crushed if interest rates rise materially. Commodity producers, including precious and base metal miners and energy companies, could also do well.

Bonds, on the other hand, performed poorly throughout most of the 1970s. Exhibit 2 shows bond yields, which move inversely to prices, rising in the first wave of inflation and spiking higher in the second. A similar outcome is possible if a second wave of inflation hits this decade, with long-dated fixed-rate debt most at risk.

Exhibit 2: Bonds underperformed in the 1970s (rising bond yields means falling bond prices) (%)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Treasury, Haver Analytics.

It’s not just inflation that could undermine bond values. Demand and supply could also play a part. Elevated government spending and refinancing existing heavy debt loads across most of the Western world should keep the bond supply high. At the same time, demand from some buyers appears to have disappeared. The US seized about USD 300 billion in Russian foreign assets (state and private property held in the West) when it invaded Ukraine in early 2022. Regardless of whether the confiscation of assets was morally justified, the unintended consequence is that nations that are not fully aligned with the US, like Russia and China, are likely now reluctant to buy Western assets. This is particularly true for government bonds, which can be easily confiscated and help fund a potential military adversary. China’s ownership share of US Treasury Securities has fallen sharply since early 2022 (Exhibit 3), with friendlier nations, including the United Kingdom and Canada, making up the difference for now. China’s central bank and those in Russia, Turkey, and India, among others, are increasing exposure to gold bullion and other assets instead.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Treasury, Haver Analytics.

It’s not just inflation that could undermine bond values. Demand and supply could also play a part. Elevated government spending and refinancing existing heavy debt loads across most of the Western world should keep the bond supply high. At the same time, demand from some buyers appears to have disappeared. The US seized about USD 300 billion in Russian foreign assets (state and private property held in the West) when it invaded Ukraine in early 2022. Regardless of whether the confiscation of assets was morally justified, the unintended consequence is that nations that are not fully aligned with the US, like Russia and China, are likely now reluctant to buy Western assets. This is particularly true for government bonds, which can be easily confiscated and help fund a potential military adversary. China’s ownership share of US Treasury Securities has fallen sharply since early 2022 (Exhibit 3), with friendlier nations, including the United Kingdom and Canada, making up the difference for now. China’s central bank and those in Russia, Turkey, and India, among others, are increasing exposure to gold bullion and other assets instead.

Exhibit 3: China steadily reduces exposure to us government bonds (treasury holdings as a percentage of total) (%)

Source: US Treasury. Data as of April 30, 2024.

Currently, developed market central banks are draining the liquidity they pumped into the financial system in 2020 with quantitative easing (printing money to buy government bonds). With governments unlikely to cut spending materially and reduced appetite for bonds from China et al, central banks may be forced to resort to quantitative easing again, with potentially positive implications for stock markets and inflation. (Exhibit 4)

Source: US Treasury. Data as of April 30, 2024.

Currently, developed market central banks are draining the liquidity they pumped into the financial system in 2020 with quantitative easing (printing money to buy government bonds). With governments unlikely to cut spending materially and reduced appetite for bonds from China et al, central banks may be forced to resort to quantitative easing again, with potentially positive implications for stock markets and inflation. (Exhibit 4)

Exhibit 4: US Federal Reserve balance sheet shrinking for now

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Data as of May 15, 2024.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Data as of May 15, 2024.